Historical Instances of Measurement and Intervention in U.S. Schools (Part II)

this article is a continuation of a research entry from the July 30, 2019 edition:

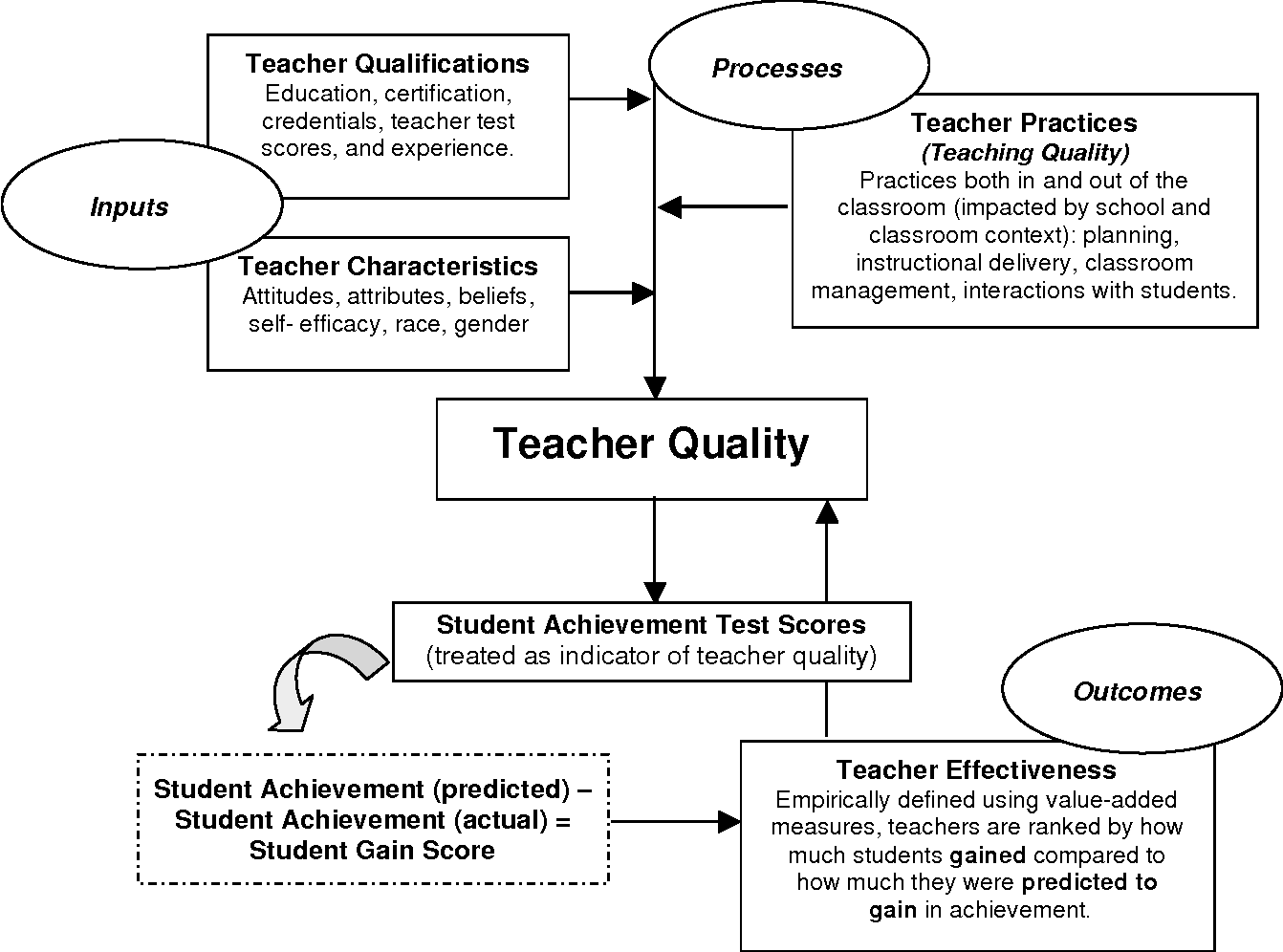

The last two decades of the twentieth century brought greater influence from the federal government, along with greater potential for teachers to become more involved in decisions that might positively affect student outcomes. The Coleman Report, A Nation at Risk, as well as subsequent federal interventions in schools have led to further reform and legislation, but not until Public Law 107 – 110, commonly referred to as No Child Left Behind, did the federal government establish such a dominant presence and focused concern with measurable outcomes. In 2001, the law was introduced to Congress as, “an act to close the achievement gap with accountability, flexibility, and choice, so that no child is left behind” (NCLB, 2002, p. 1). The legislation was in effect until a bipartisan congress stripped away the federal requirements in 2015. This law focused on standards- based reforms in education, based on the belief that by setting high standards, making outcomes for students ambitious and clear, creating and monitoring measurable goals, schools and the students within them would experience greater, more consistent achievement (NCLB, 2002). All of these improvements are based on an understanding that the role of teachers would be a primary driver for positive change. In fact, the bill requires schools to attract, retain, and develop, “highly qualified” teachers. This phrase is used more than 60 times throughout the document (NCLB, 2002).

What was most promising about this legislation was the intent to open pathways for creative, innovative, and inspired teacher practices to promote learning outcomes. Thoughtful critics of the law such as Darling-Hammond (2007) acknowledge the potential in NCLB:

While recent studies have found that teacher quality is a critical influence on student achievement, teachers are the most inequitably distributed school resource. This first-time-ever recognition of students’ right to qualified teachers is historically significant. (p. 2)

Highly qualified teachers were the intended change-agents of the hoped-for successes in NCLB, with districts being charged with,

teacher mentoring from exemplary teachers, [...] induction and support for teachers, [...] incentives, including financial incentives, [...] innovative professional development programs, [...] tenure reform, merit-based pay programs, and testing of elementary school and secondary school teachers in the academic subjects that the teachers teach. (p. 1632)

However, where federal measures aimed to reverse negative trends and improve student outcomes, the emphasis on quality teachers and teaching quality still did not receive the attention necessary to dramatically increase student achievement and narrow the achievement gap in American schools. Generally speaking, critics have pointed out that the implementation of the law was in many respects counterproductive because it (a) did not adequately account for accumulated effects of mismanaged or underfunded schools, (b) narrowed the curriculum, precisely the opposite of what sensitive and nimble teaching practices ought to do when adjusting to students in their particular situations, and (c) brought too much focus upon testing and other measurement mechanisms. The most explicit feature of the law were the unpopular standardized tests, along with tactics like “drill and kill” for test preparation, which displaced creative attempts to nurture student learning and cognitive potential (Darling-Hammond, 2007; Dee & Jacob, 201; Hanushek & Raymond, 2005; Ladd & Lauen, 2010; Rustique-Forrester, 2005; Sunderman, Tracey, Kim & Orfield 2004).

Instead of placing teachers at the center of processes for better informing learning outcomes, and placing greater emphasis on surface, deep, and transfer-appropriate thinking strategies, schools and the teachers within them succumbed to the symptoms of surface processing, short-term memorization prioritization, and the hostile environment of overtaxing students with tests (Darling-Hammond, 2007). Rather than removing barriers that continue to obstruct learning potential in schools and open more opportunities for creative thinking, more frequent Aha! experiences, as well as more holistic means of supporting the development of a child’s full potential, the American education system remained unchanged from its former industrial model of generalized goals accompanied by generalized processes.